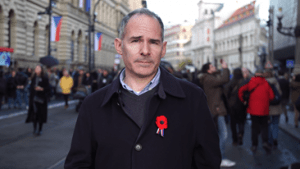

In March Prague-based BBC correspondent Rob Cameron started the Facebook group #helpyourhood as a way to help friends and family in his local neighbourhood and share information about Covid-19 in English. The group has quickly grown into a diverse professional and community forum with over 4,000 members.

In an exclusive interview for EJO Rob Cameron outlines how the group has evolved into a trusted go-to source of information and the importance of teamwork, appraising sources and a bit of humour when sharing updates and news on social media platforms.

How does your work with the Facebook group and your work for the BBC differ, is there any overlap?

How does your work with the Facebook group and your work for the BBC differ, is there any overlap?

There’s a huge difference. The group is really useful to me, I think people don’t realise how important it is to me to process and translate this information. Often I use the group as a kind of sounding board, I’ll translate something and put it out there knowing that it may end up as a radio report, a piece of track for a TV report or an online article, but it’s a perfect way of peer reviewing something.

The people in the group include people whose knowledge is vastly superior to mine and if there’s a mistake they’ll tell me. Much of the time what goes up there will at least inform what I’ll write for the BBC or anybody else, and that’s invaluable. Also, to get the tone of something right and the judge if that is the right call to make. But in other ways it’s different because I can’t make jokes on the BBC.

EJO: What motivated you to start the Facebook group?

Rob Cameron: It started as a completely random thought, because it did feel so dramatic in those early days in March. We were at a cottage near the Polish border in Eastern Bohemia when the government started shutting the borders. I’ll never forget driving back to Prague and seeing lines of Polish lorries for 40 kilometres, because they had a limited time in which they were being allowed back. And from what I was seeing in reports from China, Italy and Spain, like most people, I just assumed that if it does hit this country, we would be in a situation where we would literally be barricaded in our homes, perhaps quarantining, not being able to buy food or medicine or would be becoming ill.

So my first instinct was, why not just create a little group on Facebook, just a local group of ten twenty friends around Žižkov, who could help each other? I also thought about information, because I’m lucky in that I speak fluent Czech, but many foreign friends of mine don’t. The third reason was that I have access to some official sources, so I can text ministers and others and get an answer, so I have an unusual level of access which the BBC gives me, for which I’m very grateful.

I was putting posts up about what was happening and people seemed to appreciate it, and then it just took off with more people wanting to join. I like providing people with reliable information, but also like making people laugh, so there was also a lot of less serious stuff, including a lot of memes, which I do enjoy, especially at this horrible time.

Now it’s a combination of answers to practical questions that members can pose, a clearing house for reliable and verifiable, authentic, information, a discussion forum to talk about all these things and also laugh. We’ve had a lot of charitable things, people recommending restaurants that are struggling or charities that need help, even people who are out of work offering services.

Those things have come together into this weird online community that is primarily, although by no means solely, an expat community. I’ve consciously sought to avoid that world, and now I find myself in charge of this group which has become very much one of its main forums, so it’s really strange.

What challenges do you think that foreigners living in the Czech Republic may have with accessing information about the coronavirus pandemic?

Number one is linguistic. Number two is that even if you speak Czech, if you’re not a journalist or a person who is interested in public affairs, you may struggle finding reliable information, or knowing this is a bit dodgy, but this source is okay. Also there’s a way of parsing the information, being able to put things in proportion. If one person says something, that doesn’t mean it’s going to happen, or indicate how important it is, but if someone else says it, and then it might be important.

How do you manage the group?

It quickly became too big for me to handle on my own, as there was so much information and content to moderate. It’s all moderated content, which people seem to appreciate, so it’s generally a nice place.

People arguing, passive aggression, sniping etc., that’s not there, but it’s not there because it’s removed. It’s actively discouraged, but it’s also removed by a team of moderators which is a massive amount of work, and I have a great team of moderators who do that.

I do try and direct the content and the tone, but it’s very much a collaborative effort. We have chat groups and decide when something is not appropriate, doesn’t belong, needs to be deleted or changed. I rely on the team’s judgments more now than my own, because I don’t always make the right calls at all.

How do you think social media is influencing how people access and interpret information?

In the end it is a double edged sword, as social media always has been. It’s great that not only me, but anybody, can click on Jan Kulveit’s Facebook page, and speak to the person who invented the index that determines the tier that determines whether the shop you want to go to will be open or closed, you can write him a message and that’s fantastic. But what’s not fantastic, obviously, is all the disinformation and fake news whether it is about vaccines or anything else.

How does your work with the Facebook group and your work for the BBC differ, is there any overlap?

There’s a huge difference. The group is really useful to me, I think people don’t realise how important it is to me to process and translate this information. Often I use the group as a kind of sounding board, I’ll translate something and put it out there knowing that it may end up as a radio report, a piece of track for a TV report or an online article, but it’s a perfect way of peer reviewing something.

The people in the group include people whose knowledge is vastly superior to mine and if there’s a mistake they’ll tell me. Much of the time what goes up there will at least inform what I’ll write for the BBC or anybody else, and that’s invaluable. Also, to get the tone of something right and the judge if that is the right call to make. But in other ways it’s different because I can’t make jokes on the BBC.

Image credit: Max Pixel

Tags:Covid-19; social media; Facebook groups; BBC; Czech Republic; Rob Cameron; Jan Kulveit; expats