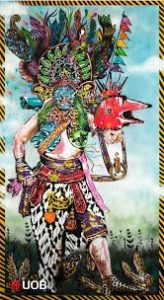

In 2019, Anagard, a street artist from Yogyakarta, Indonesia, won the UOB Painting of the year in Indonesia and South East Asia. His work, entitled Welcome Perdamaian, Goodbye Kadengkian (Welcome Peace, Goodbye Hostility), received appreciation and was exhibited at the UOB Artspace in Singapore.

The message of peace as conveyed by Anagard through his work is essential for the world, especially Indonesia, which is very vulnerable to social conflicts. Through his work, Anagard portrays an identity-based conflict that has strengthened in Indonesia, especially during the political momentum in 2014.

General elections, as a ritual of democracy, both at the national and local levels, have become a venue for the contention that has led to hostility. Political feuds were strengthened by hate speech and fake news to attack opponents through various media.

Unfortunately, the media are actually part of the political vortex that occurs. The media are increasingly biased by taking sides with certain groups. The collusion between the media and politics causes the media to be trapped in pragmatic interests. Street art as practiced by Anagard gives hope in the midst of this crucial situation. Street art can be an alternative media to convey positive messages about peace in the midst of a multidimensional crisis.

Others are enemies

The consolidation of democracy in Indonesia that has been taking place since the 1998 reforms has almost failed on its way. Political contestation in a democracy has actually become a counterproductive battle arena with democratic values because it has strengthened primordialism and identity politics. Reflecting on the 2014 elections, 2017 elections, and 2019 elections, the resilience of democracy is tested by political practices that ignore political fatsun (political ethics).

Different views and political choices lead to social conflicts that are not easy to reconcile. Worse yet, religion and ethnicity are issues that are used to attack other groups (others). The relationship that is built is antagonistic, which sees other groups as enemies. More than that, acts of intolerance have emerged in several areas, such as intimidation and persecution, demolition of houses of worship for minority groups, and others.

Two opposite faces of social media

The popularity of social media exacerbates diametric conflict. The number of social media users is around 160 million (2020). Therefore, it is dangerous if fake news (hoax) and hate speech become propaganda that weakens the construction of democracy. Social media in Indonesia is like Janus, who has two opposing faces.

On the one hand, it strengthens the democratization process when it becomes a space for public participation and representation. But on the other hand, it is also a platform for freedom that fosters hate speech. In the name of democracy, netizens can express their political ideas and views without considering factuality. Indonesian netizens are divided into two camps: lovers and haters of government and opposition groups. This segregation can be seen in the 2014 presidential election, 2017 pilkada (local election), and 2019 presidential election.

Meanwhile, the mainstream media in Indonesia have also been swept away by the wave of political conflicts. Partisan media only produce non-objective news and even disinformation. The experience of contemporary Indonesian democracy is almost the same as the political situation that occurred after the election of Joe Biden as the 46th president of the United States. Democracy as a political system that is considered the best has resulted in a political crisis.

Street Art and Peace

Street art in its various forms (stencil, graffiti, performance art, stickers, flashmob, street installation etc.) can be an alternative medium to voice peace messages (Tellidis, 2020). The city wall as a medium for street art is the most accessible gallery for the public. Street art with a political character is combined with a visual aesthetic representing everyday politics in urban spaces. Illustrations of street art as a medium to voice peace messages can be found in several countries, such as Colombia and Palestine (Tellidis, 2020).

Street art is also inseparable from memory as it appeared in Berlin. The street artworks in the Berlin walls‘ ruins are a site to treat historical events and memories in the past. Banksy, a mysterious street artist from the UK, has also criticized war and violence through several of his works, such as describing the rejection of British involvement in the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

In his work, Banksy questions the duties and obligations of the soldiers as peacekeepers. Banksy represents the icon symbolic of the sign of peace, a symbol that was originally popular in Britain as a form of protest against nuclear weapons (the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament of 1957. Now, this symbol is widely known as an international symbol of peace).

Iconicity in Anagard’s work

Anagard’s work, „Welcome Peace, Goodbye Hostility,“ is a critique of the situation that took place in Indonesia when identity politics was strong and became a threat to democracy. In his work, Anagard displays several iconicities and symbols to convey his political message.

Anagard’s work depicts a hybrid human figure in local Yogyakarta clothing (Javanese clothing), colorful, cat-headed, wearing a reog crown (a traditional art from East Java). Interestingly, this figure carries a bird’s head, an iconicity of the Rhema Hill House of Prayer in Central Java.

The house is often referred to as a multicultural house because it is a space that accommodates all religious communities. Although its main function is a church – also known as the Chicken Church, even though it is in the shape of a bird’s head-there are rooms for worshiping all religions in Indonesia (Islam, Christianity, Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Kong Hulu). Chicken Church is an inclusive space that allows all religious people to worship according to their beliefs.

Another iconicity present in Anagard’s work is the CCTV on the shoulders of the main figure. CCTV describes panopticism, which shows certain power relations. Political power linked to the superiority of certain identities (religion, race) can become a regime that continues to monitor.

As described by Michel Foucault, Panopticism is a disciplinary process in the process of governmentality (Foucault, 1975). This panopticon apparatus performs regimentation against groups that are considered as enemies. The Chicken Church brings together diversity by providing equal space for diversity.

Conclusion

Carol Rank (2008) of the Center for Peace and Reconciliation Studies has an interesting view of art’s power in peace projects. According to her:

„The power of the arts to promote peace lies in their emotive nature; the arts can help people feel the pathos and waste of war and help to instill a desire and commitment to end the war and work for peace. All of the arts have a contribution to make – music, drama, literature, poetry, dance, film – and the visual arts, such as paintings, prints, posters, sculptures, and photography.“

The presence of street art in urban public spaces, such as what Anagard did in Yogyakarta, can be an alternative medium for public literacy. Like several other works that have appeared in this city. In 2012, graffiti in one corner of Yogyakarta conveyed an idea of the significance of Jogjakarta as a Common House. The graffiti emerged as a protest against the violence and intolerant actions rampant in Yogyakarta (IVAA, 2017: 115).

Art is also a channel for marginalized groups to speak out; according to Amna Kusumo (2015), „art empowers communities to speak out“. Art activism is a reflection of the dialogue process between various voices (polyvocal). Ade Darmawan (2015), an activist at Ruang Rupa, said, „art isn’t about artistic production only. It is about building relationships and creating dialogues“. Art is not only interpreted as an aesthetic reality but a force to promote public ideas. Therefore, Street art represents a spectrum of daily problems society faces, such as things that promote peace.